The Tie that Binds for HistoInformatics2021

On September 30th, I participated in the HistoInformatics2021 Workshop, connected to the ACM/IEEE-CS Joint Conference on Digital Libraries. The workshop focused on a range of issues around data and informatics in historical research and I am very grateful for the opportunity to learn from the other papers and for the questions and feedback I received.

My paper focused on ways historians might use Katherine Bode’s model of Scholarly Editions of Literary Systems for computational text analysis in historical research.

The formal paper is published at http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2981/.

The Era of Big Historical Data

Roy Rosenzweig in his often invoked 2003 essay, “Scarcity or Abundance,” described the potential “problem of abundance” facing historians working in the digital age, where we have more materials available than our traditional historical methods are calibrated for. From published works digitized by univeristy libraries, newspapers by national libraries, and additional materials digitized by local museums and cultural heritage institutions, there is a wide variety of digital sources just waiting to be explored. Add to that the materials housed in large database vendors - such as ProQuest and Gale - and it seems reasonable to conclude that we are in the era of big historical data.

More Data, More Problems

Yet these large digital collections of historical text have a wide range of known problems. Some of the largest points of concern are:

- Unknown boundaries of the digitized data

- Unknown and highly variable OCR quality

- Instability of the data

These issues have been discussed widely by scholars across the humanities, including by Laura Mandell and Ian Milligan. Additionaly, the particular concerns surrounding OCR of historical documents was the focus on a recent Mellon-funded white paper by Ryan Cordell and David Smith at Northeastern (and now Illinois).

As historians working with digital sources, there is an urgent need for developing methods for identifying and communicating the scope and context of digitized historical sources, especially when those sources are being used in computational text analysis.

Enter the Scholarly Edition

One potential way forward on this problem has been proposed by Australian literary historian and digital humanities scholar, Katherine Bode. In her 2018 book, A World of Fiction, (as well as in a 2017 related article in MLQ), Bode introduces the framework of a scholarly edition of a literary system as a scholarly object for grounding computational text analysis in the humanities. Rather than working with digital content en masse, Bode argues for the creation of curated datasets of digitized materials and the associated metadata together with a “critical apparatus” that documents the history and production of the data as well as the history of the documentary record from which the data is derived.

Together, Bode’s scholarly edition consists of the:

- “Curated data-set” of digitized materials and associated metadata

- “Critical apparatus”

- Documentation of the history the datasets and of the documentary record

- Documentation of curation and data processes steps

Scholarly Edition of Fiction in Australian Newspapers

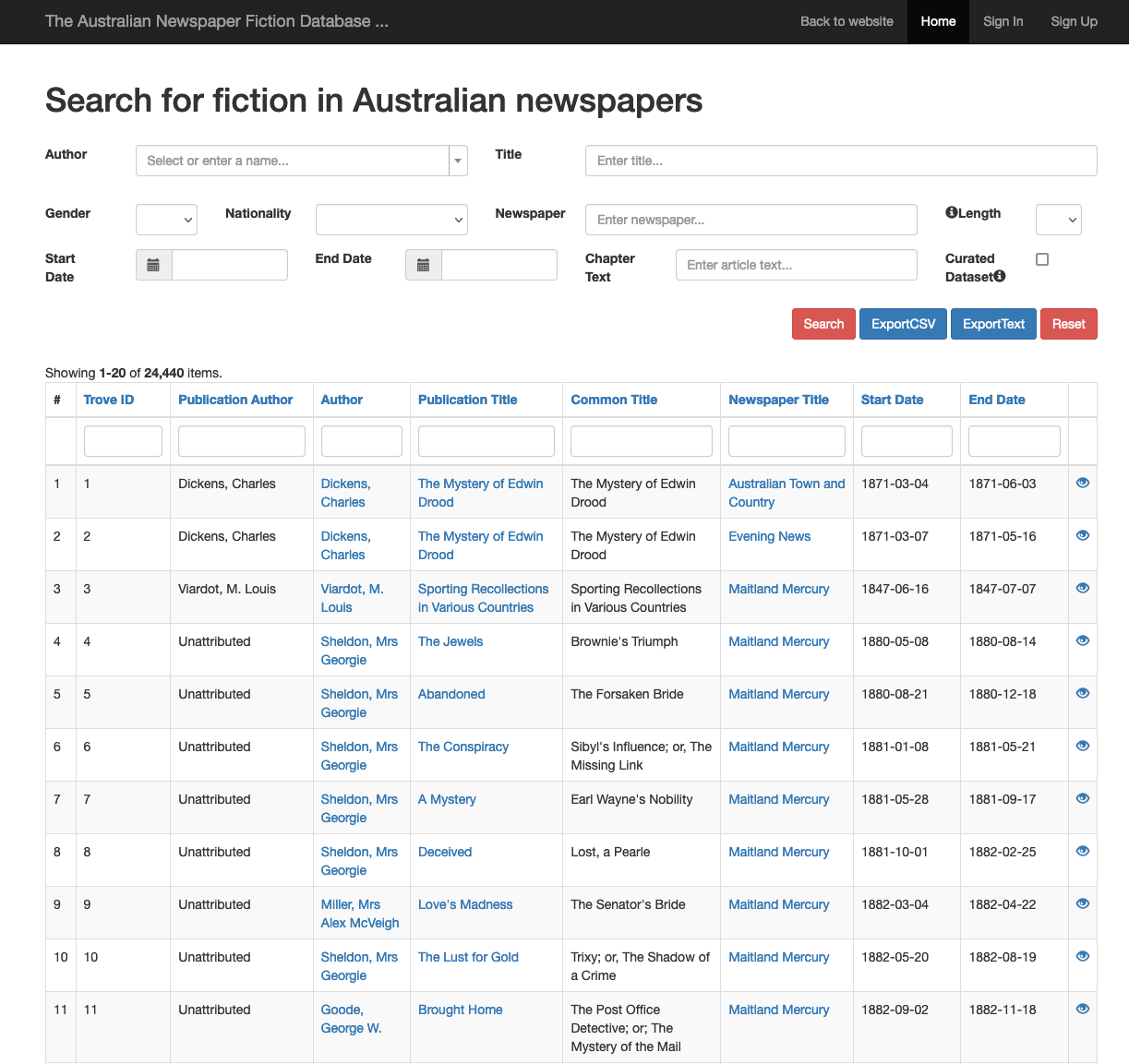

Bode’s framework is grounded in book history and literary studies and is based on her experiences identifying and analyzing reprinted fiction in the historical Australian newspapers contained in Trove. Her project exists across three different platforms and media:

- The online database of fiction examples and the corresponding metadata

- Her monograph, A World of Fiction, published with the University of Michigan

- And the digital appendix of the monograph, which houses downloadable data files derived from the database.

Together, the three pieces are an argument for and an example of a scholarly edition of a literary system, one that exposes the multiple layers of its production and that makes that resulting edition available for reuse and further investigation.

Does this model work for large historical data?

Historical text analysis projects, such as Lincoln Mullen’s America’s Public Bible or my own with the periodical literature of the Seventh-day Adventist denomination, look at language patterns in large collections of digitized historical materials, and particularly at collections where the sources are more heterogeneous than Bode’s work with reprints of fiction.

In the case of historical research with large and amorphous data, issues of data coverage and quality become especially pressing.

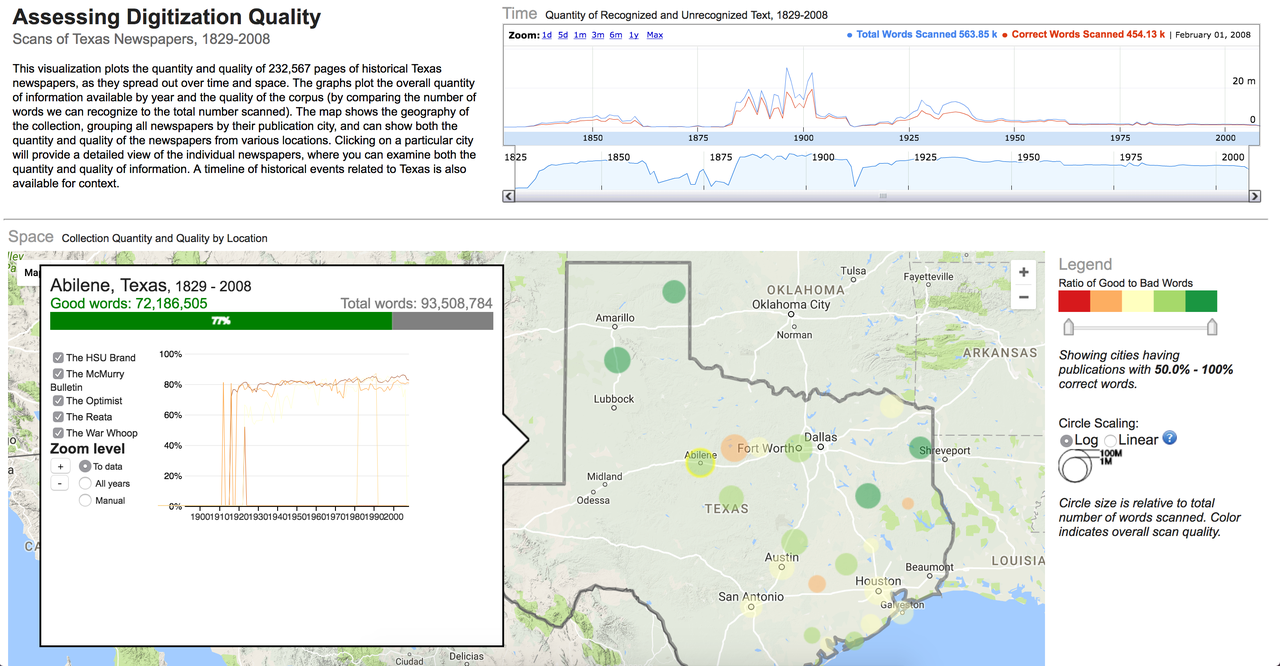

Mapping Texts Project, 2011

An example of early computational work in history that attempted to provide insight into the data quality of its sources - to document the edges and reliabliity of the data - was the Mapping Texts Project. This project focused on developing a topic-model based interface for accessing content from Texas newspapers that were included in Chronicling America. The team also created a “data quality” view (which is unfortunately not working at the moment), to document coverage and OCR quality of the newspapers and visualized by time and space, motivated in part because they needed that contextual information in order to evaluate and interpret the results from topic modeling the large collection of periodical literature. The resulting information pointed to deep gaps in the digital record, as well as significant problems with the included textual data.

The experience documented by the Mapping Texts team points to two sides of the problem facing historians working with computational analysis: the emphasis on analysis of the text (as discovery aid or for argumentation) and the largely undocumented limitations of the digital data available for use.

Building on A World of Fiction

I am interested in bringing Bode’s model into the conversation of how to do computational text analysis with historial materials. The framework of the scholarly edition and its emphasis on curated and documented datasets with information on data quality, including OCR quality and known gaps in the digitized corpus relative to the known historical record, provides a way to move toward robust interpretive analysis based upon known and documented sources.

Within the context of “big” historical data, the model of a scholarly edition of a literary system does need a few additional aspects. Particularly, the metadata and critical apparatus should include:

- estimates of OCR quality

- information on known missing data

- tighter integration of the documentation and the database

Because of issues of scale and historical happenstance, correcting all of the OCR or ensuring complete coverage are both impractical, if not impossible. Rather, by documenting the known limitations of the available data, the scholar can make strategic descisions about what to correct, what to avoid, and what questions are supported by the available data. Integrating the data with such metadata and critical apparatus also reinforces that the data is limited and conscribed, an important counterpoint to the mythology of big data.

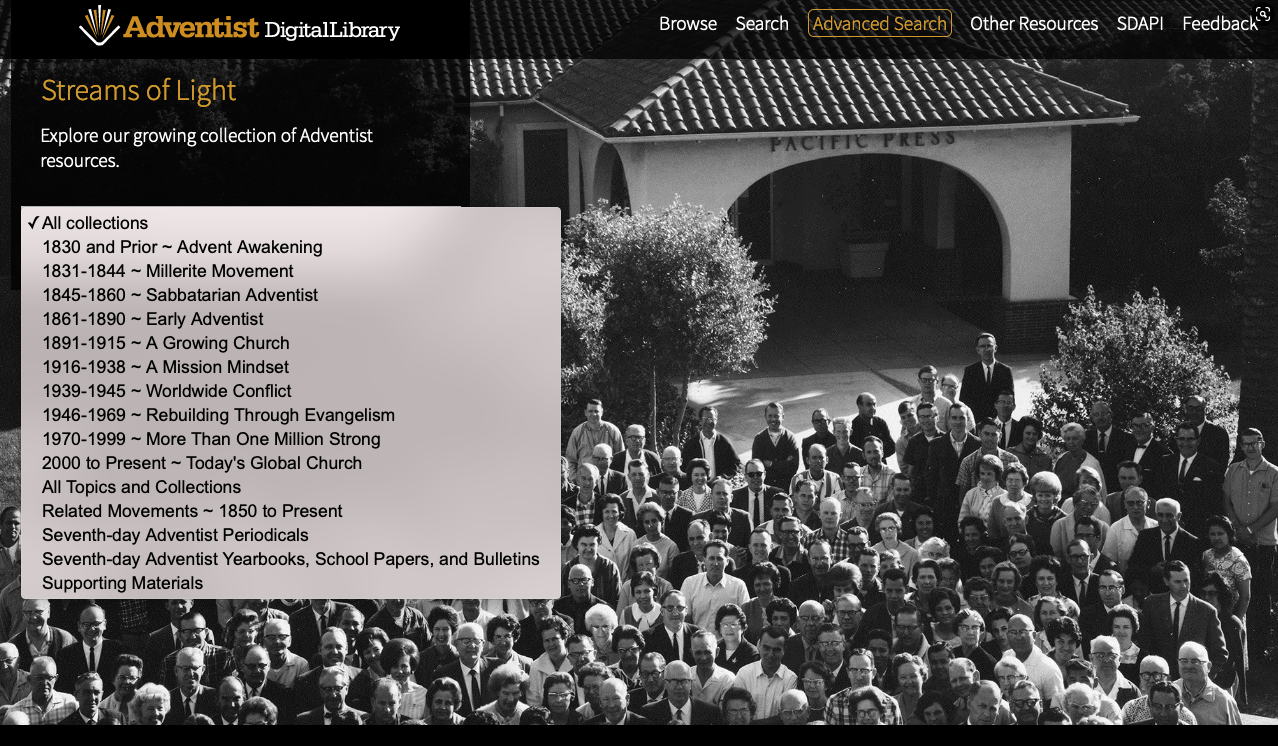

Seventh-day Adventist Print Culture

I am interested in this model because of my research with the published periodical literature of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. There are many things to say about print in the history of the denomination, but I want to focus here on their embrace of digitization. The denomination has a long history of digitizing their historical materials and making them available through the web.

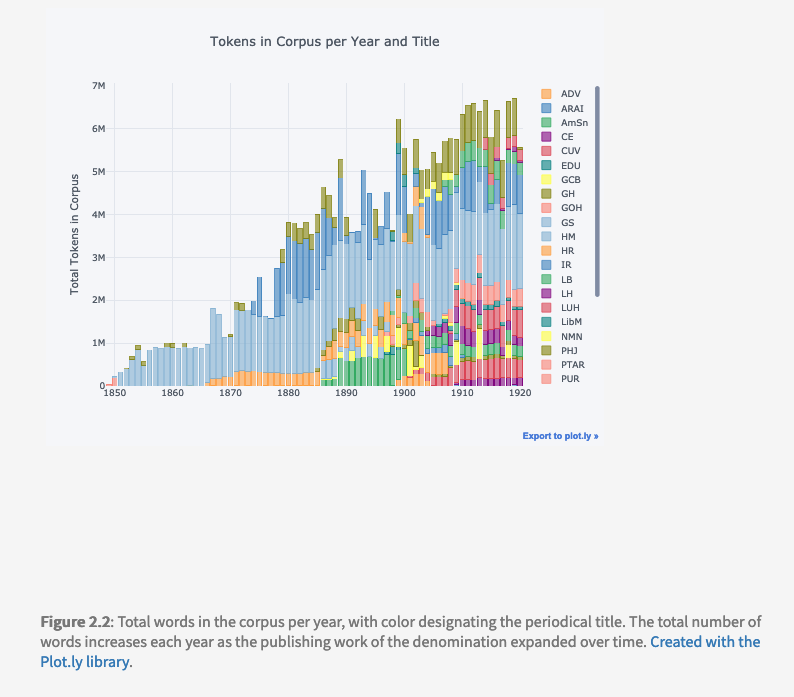

To explore patterns in language use in the history of the denomination, I selected a collection of periodicals published within the US from four regions from between 1849 and 1920. This gave me a collection of over 13,000 periodical issues with a coverage of aproximately 63% of the known major titiles produced during that period.

Toward A Scholarly Edition of Seventh-day Adventist Literary Systems

Providing information on data selection, processing, and quality proved a challenge within the format of a dissertation. I chose to focus one of my chapters to documenting the selection, evaluating, and preprocessing of those documents, using prose and visualizations. However this format is insufficient - it is not easy to read, it is not easy for reuse, and it was challenging to connect to other sections of the project.

Understanding and exploring the complex world of digitized Seventh-day Adventist print requires a more robust solution than a prose recounting.

Why a Scholarly Edition?

Adapting the model of a scholarly edition provides a number of potential adventages:

- Provides a middle space between a “data dump” and carefully prepared digital editions

- Makes it possible to work at scale across multiple “documents”

- Offers a mechanism for providing data quality information to identify limitations

- Is a stable dataset for verification and reuse

- Provides a genre of publication for this work.

Making the data for computational analysis a scholarly product in and of itself provides a way to structure and recognize the work that is involved in data creation and preparation. We know that data preparation constitutes significant work and shapes any and all data-driven analysis, but there have been few ways to recognize and evaluate that work apart apart from publications specificially interested in data, such as the Journal of Cultural Analytics. The use of scholarly editions as a model helps signal that this sort of work is at least equivalent to that involved in the construction of the text and supporting critical apparatus for a literary work.

What is Needed?

Computational historical analysis using such scholarly editions would benefit from an expanded version of Bode’s model. Such additional information would include:

- Expanded metadata related to coverage of the digitized collection vis-a-vis the documentary record and the known historical materials.

- Tools for recognizing OCR errors in historical documents, including errors in layout recognition

- An expanded interface publishing such additions that integrate the documents and the critical apparatus, including tools for visualizing included documents and the correlated contextual information

In the case of my work with Seventh-day Adventist periodicals, this would translate to generating additional metadata related to the issues and articles, formalizing my documentation of the known print materials, further evaluating the OCR of the pages and adding that information to the document metadata, and contributing to an interface for making this information readable and reusable by others.

Conclusions

Working to develop usable textual data and metadata from the scanned PDFs took up most of my time during my graduate work, and the resulting chapter, while one of my favorites in the dissertation, only touches the surface of the work involved and is an inefficient way to communicate about the data to others. Shifting toward the model of a scholarly edition provides a framework for thinking holistically about the data curated for computational analysis. And by connecting to the idea of a known scholarly output, the language of “scholarly edition” provides a way to situate this work within the broader knowledge production ecosystems.

Bringing Bode’s framework of the scholarly edition into our conversations in digital history provides another avenue for interdisciplinary cooperation. All of us who work with large digital collections need a way to document and share our work, so that we can learn from and build upon each other’s data and resulting analysis. This is a model that I think is particularly promising as it fits into the middle space between the carefully marked-up text of the digital editions often produced in literary contexts and the undefined or at least underdefined “big data” used in computational research (and widely critiqued - see Bender, Gebru, et.al., boyd and Crawford, D’Ignazio and Klein.) Computational analysis with data at scale enables historical analysis of patterns and trends that would have been nearly impossible to spot by human readers alone. But finding patterns is the easy part - evaluating those patterns and interpreting their significance requires knowledge of context and the data from which they were derived. Using the model of a scholarly edition for documenting the details and context of the data we create for computational analysis in history provides a way to make that context part of the data and so inform our own and others use of the data we compile.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: