Beautiful Soup Tutorial

(This tutorial is cross posted at The Programming Historian)

Version: Python 2.7.2 and BeautifulSoup 4.

This tutorial assumes basic knowledge of HTML, CSS, and the Document Object Model. It also assumes some knowledge of Python. For a more basic introduction to Python, see Working with Text Files. Most of the work is done in the terminal. For an introduction to using the terminal, see the Scholar’s Lab Command Line Bootcamp tutorial.

What is Beautiful Soup?

Overview

“You didn’t write that awful page. You’re just trying to get some data out of it. Beautiful Soup is here to help.” (Opening lines of Beautiful Soup) Beautiful Soup is a Python library for getting data out of HTML, XML, and other markup languages. Say you’ve found some webpages that display data relevant to your research, such as date or address information, but that do not provide any way of downloading the data directly. Beautiful Soup helps you pull particular content from a webpage, remove the HTML markup, and save the information. It is a tool for web scraping that helps you clean up and parse the documents you have pulled down from the web. The Beautiful Soup documentation will give you a sense of variety of things that the Beautiful Soup library will help with, from isolating titles and links, to extracting all of the text from the html tags, to altering the HTML within the document you’re working with.

Installing Beautiful Soup

Installing Beautiful Soup is easiest if you have pip or another Python installer already in place. If you don’t have pip, run through a quick tutorial on installing both pip and Beautiful Soup to get it running. Once you have pip installed, run the following command in the terminal to install Beautiful Soup:

pip install beautifulsoup4

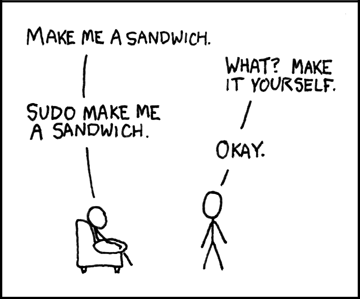

You may need to preface this line with “sudo”, which gives your computer permission to write to your root directories and requires you to re-enter your password. This is the same logic behind you being prompted to enter your password when you install a new program. With sudo, the command is:

sudo pip install beautifulsoup4

Application: Extracting names and URLs from an HTML page

Preview: Where we are going

Because I like to see where the finish line is before starting, I will begin with a view of what we are trying to create. We are attempting to go from a search results page where the html page looks like this:

</pre> <table border="1" cellspacing="2" cellpadding="3"> <tbody> <tr> <th>Member Name</th> <th>Birth-Death</th> </tr> <tr> <td><a href="http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=A000035">ADAMS, George Madison</a></td> <td>1837-1920</td> </tr> <tr> <td><a href="http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=A000074">ALBERT, William Julian</a></td> <td>1816-1879</td> </tr> <tr> <td><a href="http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=A000077">ALBRIGHT, Charles</a></td> <td>1830-1880</td> </tr> </tbody> </table> <pre>

to a CSV file with names and urls that looks like this:

"ADAMS, George Madison",http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=A000035 "ALBERT, William Julian",http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=A000074 "ALBRIGHT, Charles",http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=A000077

using a Python script like this:

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import csv

soup = BeautifulSoup (open("43rd-congress.html"))

final_link = soup.p.a

final_link.decompose()

f = csv.writer(open("43rd_Congress.csv", "w"))

f.writerow(["Name", "Link"]) # Write column headers as the first line

links = soup.find_all('a')

for link in links:

names = link.contents[0]

fullLink = link.get('href')

f.writerow([names,fullLink])

This tutorial explains to how to assemble the final code.

Get a webpage to scrape

The first step is getting a copy of the HTML page(s) want to scrape. You can combine BeautifulSoup with urllib3 to work directly with pages on the web. This tutorial, however, focuses on using BeautifulSoup with local (downloaded) copies of html files. The Congressional database that we’re using is not an easy one to scrape because the URL for the search results remains the same regardless of what you’re searching for. While this can be bypassed programmatically, it is easier for our purposes to go to http://bioguide.congress.gov/biosearch/biosearch.asp, search for Congress number 43, and to save a copy of the results page.

Selecting “File” and “Save Page As …” from your browser window will accomplish this (life will be easier if you avoid using spaces in your filename). I have used “43rd-congress.html”. Move the file into the folder you want to work in. (To learn how to automate the downloading of HTML pages using Python, see Automated Downloading with Wget and Downloading Multiple Records Using Query Strings.)

Identify content

One of the first things Beautiful Soup can help us with is locating content that is buried within the HTML structure. Beautiful Soup allows you to select content based upon tags (example: soup.body.p.b finds the first bold item inside a paragraph tag inside the body tag in the document). To get a good view of how the tags are nested in the document, we can use the method “prettify” on our soup object. Create a new text file called “soupexample.py” in the same location as your downloaded HTML file. This file will contain the Python script that we will be developing over the course of the tutorial. To begin, import the Beautiful Soup library, open the HTML file and pass it to Beautiful Soup, and then print the “pretty” version in the terminal.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup soup = BeautifulSoup(open("43rd-congress.html")) print(soup.prettify())

Save “soupexample.py” in the folder with your HTML file and go to the command line. Navigate (use ‘cd’) to the folder you’re working in and execute the following:

python soupexample.py

You should see your terminal window fill up with a nicely indented version of the original html text (see Figure 3). This is a visual representation of how the various tags relate to one another.

Using BeautifulSoup to select particular content

Remember that we are interested in only the names and URLs of the various member of the 43rd Congress. Looking at the ”pretty” version of the file, the first thing to notice is that the data we want is not too deeply embedded in the HTML structure. Both the names and the URLs are, most fortunately, embedded in “” tags. So, we need to isolate out all of the “” tags. We can do this by updating the code in “soupexample.py” to the following:

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup (open("43rd-congress.html"))

links = soup.find_all('a')

for link in links:

print link

Save and run the script again to see all of the anchor tags in the document.

python soupexample.py

One thing to notice is that there is an additional link in our file – the link for an additional search.

We can get rid of this with just a few lines of code. Going back to the pretty version, notice that this last “” tag is not within the table but is within a “<p>” tag.

Because Beautiful Soup allows us to modify the HTML, we can remove the “” that is under the “<p>” before searching for all the “” tags. To do this, we can use the “decompose” method, which removes the specified content from the “soup”. Do be careful when using “decompose”—you are deleting both the HTML tag and all of the data inside of that tag. If you have not correctly isolated the data, you may be deleting information that you wanted to extract. Update the file as below and run again.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup (open("43rd-congress.html"))

final_link = soup.p.a

final_link.decompose()

links = soup.find_all('a')

for link in links:

print link

Success! We have isolated out all of the links we want and none of the links we don’t!

Stripping Tags and Writing Content to a CSV file

But, we are not done yet! There are still HTML tags surrounding the URL data that we want. And we need to save the data into a file in order to use it for other projects. In order to clean up the HTML tags and split the URLs from the names, we need to isolate the information from the anchor tags. To do this, we will use two powerful, and commonly used Beautiful Soup methods: contents and get. Where before we told the computer to print each link, we now want the computer to separate the link into its parts and print those separately. For the names, we can use link.contents. The “contents” method isolates out the text from within html tags. For example, if you started with

<h2>This is my Header text</h2>

you would be left with “This is my Header text” after applying the contents method. In this case, we want the contents inside the first tag in “link”. (There is only one tag in “link”, but since the computer doesn’t realize that, we must tell it to use the first tag.) For the URL, however, “contents” does not work because the URL is part of the HTML tag. Instead, we will use “get”, which allow us to pull the text associated with (is on the other side of the “=” of) the “href” element.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup (open("43rd-congress.html"))

final_link = soup.p.a

final_link.decompose()

links = soup.find_all('a')

for link in links:

names = link.contents[0]

fullLink = link.get('href')

print names

print fullLink

Finally, we want to use the CSV library to write the file. First, we need to import the CSV library into the script with “import csv.” Next, we create the new CSV file when we “open” it using “csv.writer”. The “w” tells the computer to “write” to the file. And to keep everything organized, let’s write some column headers. Finally, as each line is processed, the name and URL information is written to our CSV file.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import csv

soup = BeautifulSoup (open("43rd-congress.html"))

final_link = soup.p.a

final_link.decompose()

f = csv.writer(open("43rd_Congress.csv", "w"))

f.writerow(["Name", "Link"]) # Write column headers as the first line

links = soup.find_all('a')

for link in links:

names = link.contents[0]

fullLink = link.get('href')

f.writerow([names, fullLink])

When executed, this gives us a clean CSV file that we can then use for other purposes.

We have solved our puzzle and have extracted names and URLs from the HTML file.

But wait! What if I want ALL of the data?

Let’s extend our project to capture all of the data from the webpage. We know all of our data can be found inside a table, so let’s use “<tr>” to isolate the content that we want.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup (open("43rd-congress.html"))

final_link = soup.p.a

final_link.decompose()

trs = soup.find_all('tr')

for tr in trs:

print tr

Looking at the print out in the terminal, you can see we have selected a lot more content than when we searched for “” tags. Now we need to sort through all of these lines to separate out the different types of data.

Extracting the Data

We can extract the data in two moves. First, we will isolate the link information; then, we will parse the rest of the table row data. For the first, let’s create a loop to search for all of the anchor tags and “get” the data associated with “href”.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup (open("43rd-congress.html"))

final_link = soup.p.a

final_link.decompose()

trs = soup.find_all('tr')

for tr in trs:

for link in tr.find_all('a'):

fulllink = link.get ('href')

print fulllink #print in terminal to verify results

We then need to run a search for the table data within the table rows. (The “print” here allows us to verify that the code is working but is not necessary.)

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup (open("43rd-congress.html"))

final_link = soup.p.a

final_link.decompose()

trs = soup.find_all('tr')

for tr in trs:

for link in tr.find_all('a'):

fulllink = link.get ('href')

print fulllink #print in terminal to verify results

tds = tr.find_all("td")

print tds

Next, we need to extract the data we want. We know that everything we want for our CSV file lives within table data (“td”) tags. We also know that these items appear in the same order within the row. Because we are dealing with lists, we can identify information by its position within the list. This means that the first data item in the row is identified by [0], the second by 1, etc. Because not all of the rows contain the same number of data items, we need to build in a way to tell the script to move on if it encounters an error. This is the logic of the “try” and “except” block. If a particular line fails, the script will continue on to the next line.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup (open("43rd-congress.html"))

final_link = soup.p.a

final_link.decompose()

trs = soup.find_all('tr')

for tr in trs:

for link in tr.find_all('a'):

fulllink = link.get ('href')

print fulllink #print in terminal to verify results

tds = tr.find_all("td")

try: #we are using "try" because the table is not well formatted. This allows the program to continue after encountering an error.

names = str(tds[0].get_text()) # This structure isolate the item by its column in the table and converts it into a string.

years = str(tds[1].get_text())

positions = str(tds[2].get_text())

parties = str(tds[3].get_text())

states = str(tds[4].get_text())

congress = tds[5].get_text()

except:

print "bad tr string"

continue #This tells the computer to move on to the next item after it encounters an error

print names, years, positions, parties, states, congress

Within this we are using the following structure:

years = str(tds[1].get_text())

We are applying the “get_text” method to the 2nd element in the row (because computers count beginning with 0) and creating a string from the result. This we assign to the variable “years”, which we will use to create the CSV file. We repeat this for every item in the table that we want to capture in our file.

Writing the CSV file

The last step in this file is to create the CSV file. Here we are using the same process as we did in Part I, just with more variables. As a result, our file will look like:

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import csv

soup = BeautifulSoup (open("43rd-congress.html"))

final_link = soup.p.a

final_link.decompose()

f= csv.writer(open("43rd_Congress_all.csv", "w")) # Open the output file for writing before the loop

f.writerow(["Name", "Years", "Position", "Party", "State", "Congress", "Link"]) # Write column headers as the first line

trs = soup.find_all('tr')

for tr in trs:

for link in tr.find_all('a'):

fullLink = link.get ('href')

tds = tr.find_all("td")

try: #we are using "try" because the table is not well formatted. This allows the program to continue after encountering an error.

names = str(tds[0].get_text()) # This structure isolate the item by its column in the table and converts it into a string.

years = str(tds[1].get_text())

positions = str(tds[2].get_text())

parties = str(tds[3].get_text())

states = str(tds[4].get_text())

congress = tds[5].get_text()

except:

print "bad tr string"

continue #This tells the computer to move on to the next item after it encounters an error

f.writerow([names, years, positions, parties, states, congress, fullLink])

You’ve done it! You have created a CSV file from all of the data in the table, creating useful data from the confusion of the html page.