Omeka for the Student Scholar

With software such as WordPress, Wix, and Weebly, it is relatively easy to create a website and publish content on the web. These tools help businesses and individuals draw attention to their products, services, and ideas, without having to know too much about the technologies that make up the internet.

Omeka is another software program for creating web content, but built by historians for historical content. It is used to build sites such as the Humboldt Redwoods Project and the Colored Conventions Project. These sites feature rich collections of images and documents, information about those items, and place those items within their historical contexts.

What is Omeka

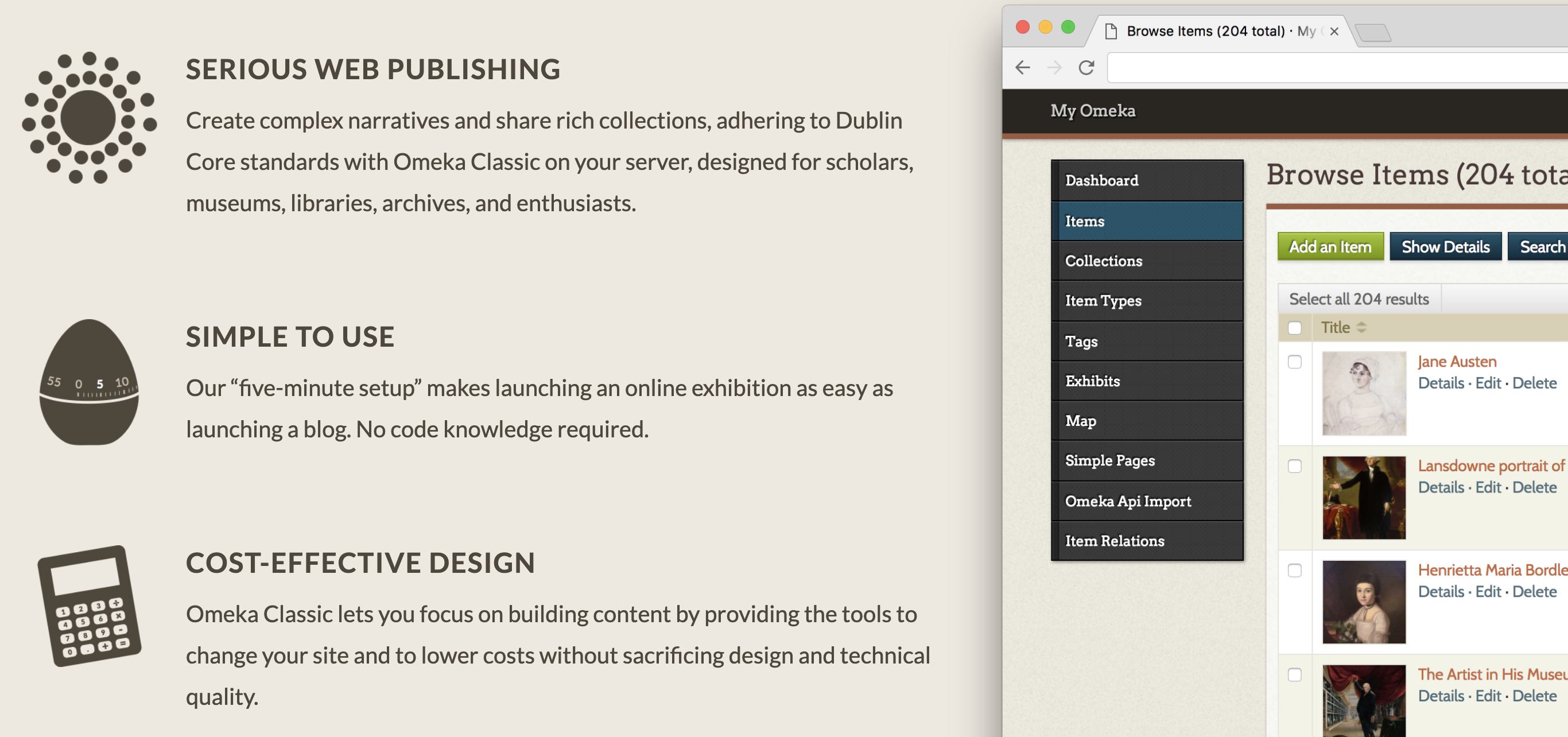

Created by researchers at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, Omeka is a content management system and website authoring tool focused on organizing and presenting historical data. Content management systems (CMS) provide an interface for managing the different types of content that make up a website - the text, the images, the design elements, and the like. In WordPress, for example, you write “Posts” and “Pages,” create “tags” and “categories,” choose your theme, and create your menus, with all of those different components coming together to create the public side of the your website.

As a content management system, Omeka provides an organizational system for creating websites based on collections of historical objects, people, and events. In Omeka, content is organized around the “item.” Think of an item as a piece of evidence, whether that be a photograph, a book, a pamphlet, a pot, a person, pretty much anything. Items can be grouped together into collections or linked together via tags. Those items can be presented using the “exhibits” feature of the site. Exhibits are similar to museum exhibits in presenting items for viewers to see with interpretive signs to help frame and interpret those items.

Within Omeka, items are described in a very specific way. In order to make data useful in the largest range of situations, people who work with cultural heritage objects, including librarians and archivists, use defined categories called metadata schemas. The schema tells you what information to collect and record about items in the world and how to format that information.

Omeka uses a schema called “Dublin Core” as the default way to structure data. Dublin Core asks for the following information in creating a description of an item:

- title

- subject

- description

- creator

- source

- publisher

- date

- contributor

- rights

- relation

- format

- language

- type

- identifier

- coverage

Your second reading for today provides definitions and examples for these terms.

Why use a metadata schema?

Metadata schemas provide a systematic way to describe objects in the world. There are a number of advantages that this brings - it makes it easier to connect items to one another (e.g., find all the books by a particular author) by encouraging consistency, and increase the chances that the data will be useful to others.

At the same time, metadata schemas formalize and solidify (reify) cultural assumptions about the world and what is significant. For example, the standard Dublin Core fields privilege formally created items, such as printed materials, and parse creative products as the work of individuals, as seen in the distinction between “creator” (though you can list multiple) and “contributor.” While there are additional or alternative fields for “people” or “events” (as creator is really not a useful data point for a person, unless we are talking about a Pygmalion sculpture), the framework in which Dublin Core makes sense is one that parses the world through a Western academic and cultural heritage frame.

There are many metadata schemas at work in the world around you. Libraries use schemas such as MARC (Metadata Authority Description Standard) and MODS (Metadata Object Description Standard) to describe resources, those who work with visual culture often use VRA Core (Visual Resources Association), and for working with digital files, there are standards for the technical metadata (data about the digital objects and how they were generated). These schemas help us organize information, but they are always already selective and interpretive.

How are we using Omeka

We are using Omeka to think about how to describe and interpret historical objects, placing them in their context historically. We will be building together a class website describing objects produced by early Seventh-day Adventists, Christian Scientists, and early Eugenicists in the US, with the goal of better understanding the ways discourses about “religion,” “science,” and “health” were interwoven and mutually constructed in the 19th century.

https://adhc.lib.ua.edu/rel120/

In the class site, you will find three collections of items with only the title and source information filled out. Your task will be to select two of these items and fill in, as best you can, the rest of the metadata. (For right now, there are only two demo items in the site - more to come!) Later on in the semester, for one of these items you will create an exhibit that places the item in its historical context - identifying who created it, why they created it, what signficance it had for them, as well as how it helps illuminate larger questions and patterns about religion, science, and health.

Working within the structure of a program like Omeka provides a number of advantages. For one, it provides a space for to collaborative build something that documents and communicates about the past. Additionally, it gives us space to think about how formal schemas structure how humans parse the world around them, showing data as constructed and powerful. And finally, it provides a way to think about how scholarship can be done outside of the traditional interpretive essay. In working to understand these items, you will need to dig into the items themselves as well as find outside information in order to place them in their historical contexts. And that is the work of history.